On this day in 1873, George Caleb Bingham in Kansas City, Missouri, wrote to James S. Rollins in Columbia, Missouri, “I will call by as I go east, and assist in the proper framing of your portrait. It will be well to put on a new strong stretching frame, with another good thick canvas behind it to give that on which the portrait is painted additional strength. ” ((George Caleb Bingham, “Letter to James Sidney Rollins,” October 26, 1873, Kansas City, Missouri, in Lynn Wolf Gentzler, editor, Roger E. Robinson, compiler, “But I Forget That I am a Painter and Not a Politician”: The Letters of George Caleb Bingham (The State Historical Society of Missouri and Friends of Arrow Rock, Inc. 2011), 358.))

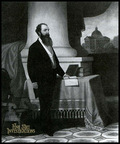

The portrait would have been the large, full-length painting for which only the modella now exists. Bingham also painted simply the head and shoulders of the larger painting, now owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri. Especially in this zoom-able link, the artist’s respect and affection for his friend of 40 years can be seen. Unfortunately, the popular overly hirsute style of men’s facial hair in the 1870s hides the lower part of his face.

Oil on Canvas, 33 x 30 inches

Private Collection

Through only the upper part of the face, Bingham shows us Rollins through his eyes. we can see the artist’s respect and affection for his subject. How artists achieve such effects is beyond me, but not for Bingham, who described his process:

There are lines which are to be seen on every man’s face which indicate to a certain extent the nature of the spirit within him. But these lines are not the spirit which indicate any more than the sign above the entrance to a store is the merchandise within. These lines upon the face embody what artists its expression, because they reveal the thoughts, emotions, and to some extent the mental and moral character of the man. The clear perception and practiced eye of the artist will not fail to detect these; and by tracing similar lines upon the portrait, he gives to it the expression which belong to the face of his sitter, in doing this, so far from transferring to his canvas the soul of his subject, he merely gives such indications of a soul as appear in certain lines of the human face; if he gives them correctly, he has done all that Art can do.((George Caleb Bingham, “Art, the Ideal of Art and the Utility of Art,” March 1, 1879 in Gentzler, 504.))

The consummate skill that can be seen in this portrait belies the standard assessment that Bingham painted his best work in the 1840s. Indeed, he painted the majority of his genre pieces in that time frame. The statement demonstrates the preference of art historians for genre and historical art and which places portraiture on the bottom rung of a metaphorical ladder. When portraiture is included in the artist’s oeuvre, one can see the skillful maturity of his later work.