Discovering History through Art

Historians usually add a painting as an illustration. Fine Art Investigations uses portraits as an entry point to history. An example is the stories behind the recently re-discovered portraits of the Dunnicas.

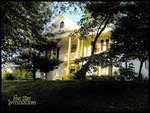

The first part of their biography briefly described American expansion in the west after the War of 1812. Back when the Western frontier was central Missouri and the basic mode of transportation was a keel boat. The story resumes after William Franklin Dunnica established a successful merchandising company beside the Missouri River in Chariton / Glasgow, Missouri, married, and built a large home on a hilltop above the town.

George Caleb Bingham, William Franklin Dunnica, ca. 1837

Oil on Canvas, 24 x 29 inches Private Collection

George Caleb Bingham, Martha Jane Shackelford, (Mrs. William Franklin Dunnica), ca. 1837

Oil on Canvas, 24 x 29 inches Private Collection

First Years of Marriage

William Franklin Dunnica was a 30-year-old merchant in Glasgow, Chariton County, Missouri, in 1837 when George Caleb Bingham painted the recently re-discovered portraits of him and his 17-year-old wife, Martha Jane Shackelford. A year later, the Missouri militia called Dunnica and other residents of Chariton to neighboring Carroll County.

In Carroll County, long term residents and newly settled Mormons were ready to battle. Among the officers were Dunnica and Judge James Earickson. Rather than shed blood, both men urged compromise. Earickson negotiated a peaceful retreat for the Mormons, who re-located to Caldwell County.((O. P. Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri (National Historical Company. 1883), 54-56; Background information from Stephen C. LeSueur, “Missouri’s Failed Compromise: The Creation of Caldwell County for the Mormons.” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 2 (2005): 113-44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289934, accessed February 2019.))

As her husband forestalled war, Martha Jane Dunnica was at home with their newborn first child, Jane Eliza (1838-1858). As was customary at the time, Martha Jane gave birth to a child about every year and a half: Ann Meyrick (1841–1863), Mary Louisa (1843–1930), Thomas Shackelford (1845–after 1880), Theodore (1847–1851), Locke (1851–1852), and Sydney (1855–after 1880).

Business and Civic Leader

William Dunnica operated his mercantile company in Glasgow for more than twenty years, partnering with various other businessmen. Simultaneously, he found foreign markets for tobacco locally grown by William Daniel Swinney and others. He also clarified titles for landowners. Among his clients was Kentucky Congressman Henry Clay.((O. P. Williams. & Co., History of Howard and Cooper Counties, Missouri (National Historical Company. 1883),437; Available documentation does not clarify whether Dunnica was the official or unofficial registrar for land titles; The Papers of Henry Clay: The Whig Leader, January 1, 1837-December 31, 1843 (University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 453.))

Methodist Church

When the Methodist church was organized at Glasgow on December 28, 1844, the trustees included William Dunnica and William Swinney. Nationally, the issue of slavery had split the Methodist church into two branches, the northern and the southern. Less than six months after the founding of Glasgow’s First Methodist Church, trustees had to decide which division to join. Dunnica, like the majority of Missourians, who if not southern-born, had southern roots, owned slaves. His numbered 10, and ranged in age from 1 to 50, and lived in three slave houses, which indicated decent living situations in family groups. With the rest of the trustees, he voted for membership in the Methodist Episcopal Church South.”((Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri, 354.))

From April 1849 until December 1852, William Dunnica held the position of postmaster, a prestigious federal appointment at the time. In 1858, after Glasgow citizens organized a branch of the Exchange Bank of St. Louis with Dunnica as its leader. In the midst of William’s successes, Martha Jane died in childbirth on August 31, 1858. Their seventh child died with her.

Second Wife

Almost two years after Martha Jane’s death, on June 30, 1860, William married Leona Hardeman Cordell (1823-1905) in St. Louis, Missouri. Their marriage brought together two successful families. Leona was the daughter of John Hardeman (1776-1829) a merchant, trader and businessman who was also a famed amateur botanist. Her first husband, Richard Lewis Cordell, had abandoned her and their two children. Her marriage to Dunnica would last until his death in 1896 – a total of 36 years. They had three daughters.((William E. Foley, “Hardeman, John,” in Lawrence O. Christensen, William E. Foley, Gary Kremer, and Kenneth H. Winn, eds., Dictionary of Missouri Biography (University of Missouri Press, 1999), 370-371. George Caleb Bingham portrayed Leona’s brother, John Locke Hardeman, circa 1855, which is owned by the State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia, http://digital.shsmo.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/art/id/245/rec/1, accessed January 2019.))

In 1863, with J. S. Thomson, Dunnica purchased Glasgow’s Exchange Bank. The town’s other bank was owned by W. D. Swinney and the Birch family.((Ibid., 234, 211; United States Census Bureau, Eighth Census of the United States: Slave Schedules, “W. F. Dunnica,” Chariton-Glasgow, Howard, Missouri, August, 1860, column 2, lines 3-13.))

Civil War

The Battle of Glasgow

In the autumn of 1864, Union forces led by Colonel Chester Harding, Jr., occupied Glasgow. Confederate General Sterling Price ordered an attack on the town. Expecting a confrontation, Colonel Harding ordered his men to dig rifle pits on one of the highest points in town — about 225 yards away from the Dunnica home, Dunhaven.((Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri, 288; J. Y. Miller added specific leadership details.))

Photograph by J. Y. Miller

General Joseph. O. Shelby was in overall command of Confederate forces during the battle. Joining him was Brigadier General John Bullock Clark from nearby Fayette, Missouri. On October 15, 1864, the Battle of Glasgow began.((Williams, History of Chariton and Howard Counties, Missouri, 288; J. Y. Miller added specific leadership details.))

On the day of the battle, Shelby first directed his fire against the steamer Western Wind, a barracks for Union soldiers. The ship, lying at the wharf, was soon disabled and abandoned. A Confederate battalion took control of Dunhaven. Shelby turned his guns on the City Hall that Union forces used as a commissary depot. Before 10:00 am, all the garrison defending the town was compelled to take to their rifle pits. The house had ten openings fronting the pits. As rebels fired out, sharpshooters in the pits fired over 300 bullets into the house. The Confederates were closing in on the rifle pits when the City Hall was set on fire. A strong wind blowing from the northwest spread the fire. Twelve or fifteen houses burned to the ground. With over 50 casualties on each side, Harding surrendered to Clark at one in the afternoon.((Williams., 288-289))

After the Battle

Bloody Bill Anderson

The victors disarmed and paroled 27 Union officers, including Harding. The defeated men knew that the month before, only 50 miles away, Bloody Bill Anderson’s gang had murdered 23 unarmed Union soldiers on a train stopped at the station in Centralia, Missouri. Congressman James Sidney Rollins, George Caleb Bingham’s good friend, had been on the same train and barely escaped. Fearing that if they remained at Glasgow without weapons, they would meet the same fate, the prisoners requested an escort to the federal camp in Boonville.((Ibid. Daniel N. Rolph, My Brother’s Keeper (Stackpole Books, 2002) referenced in J. Y. Miller, “LT James W. Graves – A Story of Courage and Honor,” Battle of Glasgow History, Lewis Library, Glasgow, Missouri, http://www.lewislibrary.org/BOGGraves.html, accessed January 2019.))

Lieutenant James W. Graves

Confederate Lieutenant James W. Graves commanded the escort of some 70 men from Company H, 3rd Missouri Mounted Infantry. Waiting at a fork in the road were Bloody Bill Anderson and some 100 of his guerrillas, dressed in the blue uniforms of fallen federal forces. When four of Anderson’s men rode ahead and demanded the parolees, Graves was not fooled by their disguise. He is reported to have said, “Tell Bill Anderson that his damnable proposal is too infamous for me to consider for an instant. We are Confederate soldiers, and he and his men are murderers and thieves.”(Ibid.))

The lieutenant gave the Union officers the option to flee on their own, but the men chose to remain with the rebel Army. Graves re-armed them. Waving a flag with stars and bars and a flag with stars and stripes, the soldiers from both sides prepared to fight Anderson and his men. But like most bullies, when confronted courage, the guerrillas retreated.((Ibid.))

The next day, the escort met a federal patrol and safely returned the parolees to the Union Army. In his report of the battle, Colonel Harding wrote, “I desire particularly to acknowledge the assiduous care which Lieutenant Graves of the Third (rebel) Missouri Volunteers, commanding our escort, bestowed upon us and the good behaviour of his men. Had they been our own troops we could not have been better treated.” After the war, the former officers honored Graves with a medal.((Ibid.))

William Quantrill

While Bloody Bill Anderson was on the outskirts of town, William Quantrill was in Glasgow itself. The year before Quantrill and his Raiders had murdered 200 men and boys in Lawrence, Kansas, before setting fire to the abolitionist town. In Glasgow, Quantrill claimed to have been the first man to reach the rifle pits after the surrender. Either Shelby or Clark told him he was not aware of Quantrill’s presence at any time during the engagement but only saw him afterwards.((Williams, 289.))

On the second evening after the battle, Quantrill commanded two of his men to go to Dunhaven and bring William Dunnica to his bank. There, Quantrill coerced Dunnica to unlock the bank vault and safe. The raiders left with $21,000. What they didn’t know was that the day before, Dunnica had buried $32,000.((Ibid.))

Dunnica Saves His Friend

The next week some of that buried money rescued Dunnica’s friend, tobacco farmer Benjamin Lewis. Lewis supported the Union and had offered a $6,000 reward for Bloody Bill Anderson. Riding into the devastated town of Glasgow, Anderson broke into Lewis’ home and ordered him to give him the $6,000. Lewis did not have the amount on hand. Anderson beat and tortured him, swearing that he would not stop until he had the full $6,000, whether from Lewis himself or from his family and friends. Dunnica came with the rest of the money and Anderson released the badly injured Lewis. Two years later Lewis died from those injuries, but without Dunnica’s foresight and help, he would have died that day.((J. Y. Miller, Battle of Glasgow History, Lewis Library, Glasgow, Missouri, http://www.lewislibrary.org/BOG.html, accessed January 2019; email correspondence with J. Y. Miller, January 28, 2019.))

Last Years

William and Leona Dunnica repaired their home and replaced their bullet-ridden furniture. Under the clapboard of the house, the bullet holes can still be seen. The Thomson & Dunnica Bank survived the war and continued until 1877 when it merged with Howard County Bank. Dunnica again led the financial institution until he retired in 1881 at the age of 74.

In 1883 a biographer wrote, “Mr. D. has been an enterprising and public-spirited citizen and has contributed very materially to the general prosperity of Glasgow and surrounding country. He has never sought or desired office, although he has several times been induced to accept minor official positions that did not interfere with his business. His desire has been, so far as public affairs are concerned, to make himself a useful factor in the material development of the county with which he is identified. The biographer admonished his readers that the life of W. F. Dunnica proved that “intelligent industry and frugality, united with upright conduct, cannot fail to bring abundant success.”((Ibid.))

William Franklin Dunnica lived to the age of 88. He died on April 28, 1896. Leona died in Glasgow nine years later on February 28, 1905. They are both buried in Glasgow’s Washington Cemetery beside Dunnica’s first wife, Martha Jane Shackelford Dunnica.

With the re-discovery of the companion portraits of William Franklin Dunnica and Martha Jane Shackelford, we now have another example of Bingham’s artistry. We also have a window into the past that brings history to life through the details of the sitters’ lives.